Beyond a doubt, Legio Maria — now formally Legio Maria of Africa Church Mission — founded in Kenya around 1962 is the largest of the groups with an alternative pope. While it is difficult to compute membership, the Kenyan government estimates that there are as many as 3 or even 4 million Legios in Kenya alone. Legio Maria should not be confused with the Roman Catholic lay organisation, Legion of Mary, also known as Legio Mariae. Still, many of the founding members of the Kenyan Legio had backgrounds in the Legion of Mary and viewed it as a precursor to their movement.

Established in the Nyanza province in the early 1960s, Legio Maria soon spread to other parts of the country and abroad, both within Africa and, to a lesser extent, overseas. Legio Maria has its roots in Roman Catholicism but, following the metropolitan model, has developed its own ecclesiastical hierarchy, including a pope. The Legios use the traditional Latin Order of the Mass in a pre-1962 version, but also have a clear focus on charismatic gifts available to ordinary believers, not only to holders of formal offices.

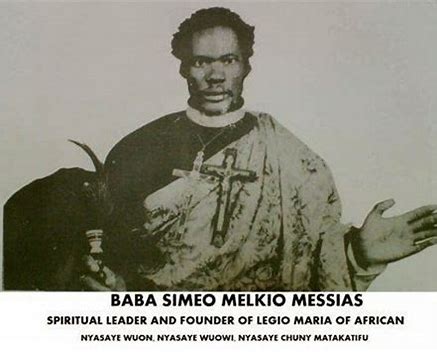

Legios believe that the founder, Simeo Ondeto (1926?–1991), was divine. He was the Second Coming of Christ. Therefore, the faithful refer to him as Baba Messias, Baba Simeo Melkio, and similar varieties of that name, ‘Baba’ meaning Father. They also revere Mama Maria or Bikira Maria († 1966), originally known as Regina Owitch, whom they see as the Virgin Mary and Baba Messias’s spiritual mother. Because of their supernatural origins, Baba Messias and Mama Maria held unique positions.

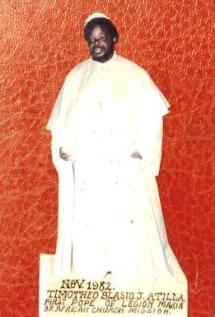

The two soon developed a formal church organisation, including a pope: Timoteo Blasio Atila (sed. 1964–1998). During Baba Messias’s life, Atila had a rather low-key presence, but he was destined to be the successor of Simeo Ondeto when the latter returned to heaven. After Atila died, there have been two other official pontiffs: Pope Maria Pius Lawrence Jairo Chiaji K’Adera (1998–2004) and Pope Raphael Titus Otieno (2004–present). However, during the 2010s, Romanus Alphonsus On’gombe (2010–2020) claimed the papacy. His claim was accepted by large groups, and the papal issue continues to divide Legio Maria, as Pope Lawrence Ochieng now claims the papacy since 2020.

Though some available lists of modern ‘antipopes’ include Pope Atila and, less often, his successors, the Legio Maria is seldom studied in the same way as the European- and North American-based churches that have alternative popes. If discussed at all, they are included in the particular category of African-inititated churches (AICs). Still, Legio Maria considers itself the reformed Catholic Church for the current era. It has African roots, but it is not just for Africans. The official name they assumed in 1979–the Legio Maria of African Church Mission–underlines this self-understanding. In short, Legio Maria makes universal claims and asserts that it is more inclusive and catholic than the Roman Catholic Church.

Sources and Earlier Research

When searching for source material, it soon becomes evident that Legio Maria is not a text-centred religious group. Few official or semi-official church publications exist. In 2010, the contending Pope, Romanus On’gombe, published a booklet called Baba Simeo Melkio: The Glory of God, and a Legio deacon, Tobias Oloo, is an active author who has written much about the Church’s beliefs and practices. The most systematic of his works is The Lord Returns: This is the Gospel of Simeo Melkio, the Glory of God, a book published in the mid-2010s. It is a chronological narrative, modeled on the New Testament gospels, that recounts Simeo Ondeto’s life story and mission. Oloo also has a website that includes many other apologetic texts, as well as liturgies, prayers, and songs. These are important sources for my presentation.

Still, these written works represent a late and relatively systematised version of the teachings that do not necessarily reflect the development over the years or the views of Legios at large. It is not the official position. Thus, to get a broad image of Legio Maria, oral sources and field studies are essential. I have not done any research of that type, but I rely on other scholars’ work.

A pioneering researcher was sociologist Audrey Whipper, who conducted a field study of Legio Maria in 1964–1965. In later decades, anthropologists and theologians have spent long periods with Legios, trying to understand the Church and its teachings and practices. In the oral history they have documented, the exact chronology is not a crucial factor, and, unsurprisingly, there are many different, sometimes conflicting narratives among both clergy and lay people.

Several researchers also attest that it has been difficult and time-consuming to gain access to informants among the Legios. At least partly due to such factors, there are relatively few scholarly studies on Legio Maria. Unfortunately, many of the most important works are PhD dissertations that have remained unpublished. However, in most cases, the authors have also published related articles and book chapters.

The earliest comprehensive study on Legio Maria was Roman Catholic missionary Peter Dirven’s doctoral dissertation, which was defended at the Gregoriana University in 1970. Based on interviews and press material, the study certainly has its merits. However, his starting point is problematic from a religious studies perspective: the Roman Catholic Church is right, Legio Maria is wrong, and the latter poses a serious threat to the Roman Catholic Church. Later researchers have devoted much space to criticising Dirven’s observations and arguments.

One of them was anthropologist Nancy Schwartz. Her massive PhD dissertation (1989) made a substantial contribution to our knowledge of the Legios. In the thesis, based on a more than three-year-long field study and on almost a thousand interviews, she focuses on historiography and Legio narratives, particularly on the practice of glossolalia. Schwartz critically and convincingly evaluated earlier research, not least Dirven’s study. Though her thesis remains unpublished, in the 1990s and early 2000s Schwartz produced several articles on Legio Maria, which, together with the thesis, are of paramount importance for any study of the Church.

In the 1990s, theologian Teresia M. Hinga wrote a doctoral dissertation on the roles of Legio women, and Ruth Prince studied Legios’ interpretations of illness and healing. Both studies include valuable contributions. About the same time, theologians Scott Moreau and James Kombo published an introductory article about Legio Maria. Although it is a brief general overview, they use interviews and other materials to evaluate earlier interpretations, making it a study worth considering.

In recent years, Matthew Kustenbader has published a general study on Legio Maria’s early years as well as a biographical article on Guadencia Aoko, one of the important actors in that period. He combines fieldwork with a study of press material, but also uses Audrey Whipper’s unpublished field reports from the 1960s. Among later, more specialised works, one could mention musicologist Shitandi Wilson Ol’leka’s 2010 book on Legio hymns.

Beginnings

Thus, researchers have devoted much effort to investigating the background and origins of Legio Maria. It is a complicated matter, as there are so many different, partially conflicting narratives. For example, there is no consensus about when Legio Maria was founded. Adherents and scholars alike have suggested 1961, 1962, or 1963.

In this context, it is relevant to consider what ‘founded’ means. Was it when Ondeto and his followers broke ties with the Roman Catholic Church and chose a pope of their own? In that case, the foundation took place in 1964. However, if foundation means that a sizeable group of adherents gathered around Simeo Ondeto, Mama Maria, and Gaudencia Aoko and they began to establish an organisation, the date is either 1962 or 1963. According to several of the researchers, many adherents claim that the Legio Maria was ‘first heard of’ in 1962, the year of Kenya’s independence. However, Ondeto’s ministry began already in the late 1950s. What is entirely clear is that Legio Maria originated among the Luo in Nyanza Province, Western Kenya.

As with the foundation, there is no consensus on when Simeo Ondeto was born, and estimates range from the early 1910s to the mid-1920s. In a gerontocratic society, it could be tempting to claim that a person is older than he or she was or that one did not know it or found it relevant. Still, today, a Church representative, Deacon Oloo, claims he was born as late as 1926. Moreover, from photos of Ondeto, it seems reasonable that he was born around that time.

Although Legios believe that Ondeto had a divine origin and that he is the second person of the Trinity, most assert that he was born into the home of Obimbo Joseph Msumba and Margret Aduwo, who lived near Awasi in Kisumu County. Combining the preternatural with the natural, Oloo writes ‘After descending from the clouds and taking up flesh as a child’, Ondeto joined the family as the third of five children.

According to many Legio narratives, Ondeto was known for his early miracles, or in Oloo’s words: ‘When he was still a child, Simeo Melkio [one of his messianic titles of Ondeto’s] could surprisingly appear as an old man; and sometimes he could appear to different people in different places at the same time.’ In other words, they believe he had the charismatic gift of bilocation and could change his appearance by mystic means. From an early age, Ondeto was a herdsboy but left home before he was a teenager. Information about his youth is sketchy, but in 1952, he was baptised in the Roman Catholic Church, which had gained a rather strong presence in the Nyanza province. At baptism, he received the name Simeo.

Ondeto served as a catechist at the mission station Nyandago, which was run by Mill Hill missionaries. Soon, however, he concluded that African laypeople had a too marginalised role in the Roman Catholic Church, not least in the divine cult. This realisation gradually led him to a more independent, active ministry. He was certainly not alone in wanting a more active, charismatic form of Christianity. Still, for several decades, such movements typically emanated from Protestant missions, not from the Roman Catholic Church, though it was by no means unique.

According to some Legio narratives, Ondeto died in 1958 but returned to life after three days. After that, he realised that he had a great mission. Soon, he became a well-known healer and prophet who could drive out evil spirits, and he travelled throughout southern Kenya and northernTanzania. Not surprisingly, the Roman Catholic Church authorities grew increasingly critical of him and rejected his independent, unorthodox ministry. Over time, the local bishop formally excommunicated him, though the exact date is unknown, likely not until the early 1960s.

Critical sources generally claim that he was first excommunicated and then founded Legio Maria. Still, a common view among Legio members is that it was not Ondeto who left the Catholic Church, but the missionaries. In an interview with Nancy Schwartz, a lay member stated: ‘They threw the Messias (Simeo Ondeto) out. He was a Catholic, and they threw him out. He did not break away.’

Simeo Ondeto’s preaching and healing activities coincided with the fight for Kenyan independence. In both the 1970s and today, some Legios claim that he was part of the Mau Mau movement, at least in a spiritual sense. The Mau Mau guerrilla movement was active between 1952 and 1960 and fought the colonial power, but most of its members were from Kenya’s largest ethnic group, the Kikuyu.

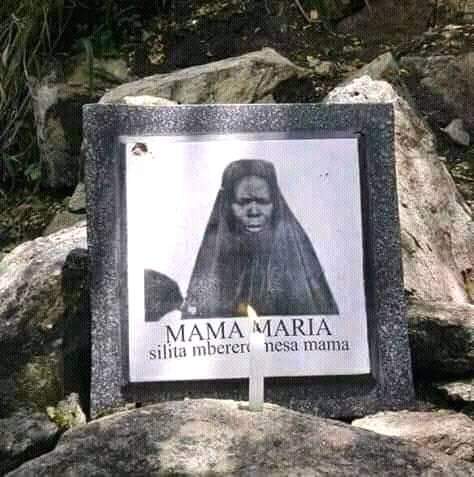

Apart from Simeo Ondeto, the most crucial figure in the foundation of Legio Maria was Mama Maria. Her real name was Regina Owitch, and she was said to have been born as early as the 1870s, though the age may have been exaggerated. She was generally believed to be an African incarnation of Bikira Maria, i.e., the Virgin Mary. Her supernatural origin seems to have been accepted already in the early 1960s. According to Legio historiography, Ondeto and Bikira Maria met at the beginning of 1962 in Suna, where she declared him her ‘spiritual son.’ Often, their first meeting is considered the starting point of the Legio Maria.

There are many narratives about Mama Maria’s background, some much more elaborate than others, but a common denominator is that they combine her local and global activities. One common story is that she first arrived in Lake Victoria from heaven at an unknown date. More developed narratives claim that her arrival was the result of a heavenly council that decided Jesus would return to Earth. At his second coming, Christ would appear as a black man, Simeo Ondeto, and be sent to the oppressed Africans. The Virgin would also return to Earth as a black woman to help her son in his mission. According to Oloo, in the mid-1960s, Mama Maria recounted

After the dismissal of the Great Assembly of Sayun [a place in heaven], I boarded my jet to the Earth. Upon arrival, my plane hovered over the Earth for quite a while. It surveyed different continents of the world before landing. And as my jet flew past India, I directed my pilot, saying: ‘Do not land there. I have been there before. Take me back to Africa.’ So my jet arrived in Africa and landed in East Africa, in Lake Victoria.

After Mama Maria had arrived in Lake Victoria, she went up from the lake and travelled around the world. She went to Israel, Europe, the Americas, and other places. According to a widely circulated narrative, she appeared to the three children at Fatima, Portugal, in 1917. In the visions, however, she did not appear dark-skinned. At Fatima, she confided three secrets to the seer Lucia. Of them, only two were made public. According to many Legios, the Third Secret, which Pope John XXIII chose not to disclose by 1960, was the prophecy of the arrival of the new Messiah, Simeo Ondeto, and of Africa’s role in the Salvation History. In his book about the life of Baba Messias, Odoo writes:

The third secret was about the trips of the glory of God [i.e. Ondeto, Baba Messias] on Earth. Lucia saw a man dressed in a red cap like that of a bishop. The man walked the Earth, teaching people and gathering them together. The man appointed bishops, priests, and nuns; and many people followed him until he climbed up a steep hill. When the man in the secret vision reached the hill, he erected crosses made of unrefined wood. – – – Indeed, the Fatima Secrets were prophetic of the coming of the Glory of God, Simeo Melkio.

In the 1920s and 1930s, after appearing to the children at Fatima, Mama Maria returned to Kenya and wandered through Luo villages, where she was generally regarded as a crazy person. Still, towards the end of the 1930s, she began to reveal herself to individual Roman Catholics, announcing that they were the Virgin Mary. Usually, Mama Maria appeared as Our Lady of the Rosary and stated that her son had returned to Earth and would soon begin his public ministry. She particularly approached members of the Legion of Mary, the Roman Catholic lay organization of Irish origin established among the Luo in the early 1930s.

According to many Legios, Mama Maria was Ondeto’s forerunner, a new John the Baptist.In the early 1950s, Bikira Maria appeare to have stayed in Maria (Mariam) Ragot’s home in Nyabondo. In 1952, Ragot, who was active in the Legion of Mary, began preaching and baptizing and founded Dini ya Mariam (Swahili: Mary’s religion), which at least some Legios today understand as a precursor to the Legio Maria. Ragot developed a clear anti-missionary stance; the government understood her as a dangerous troublemaker, and both she and her husband were forced to leave the region, placed under house arrest, and imprisoned. This situation persisted for at least six years, from 1954 to 1960.

Apart from Odeto and Mama Maria, the third essential person in the foundation and early growth of Legio Maria was Gaudencia Aoko (1943–2018), a Luo woman born in Awasi, Kisumu County, Nyanza, who was baptised a Roman Catholic in her teens. She married at a young age, but her two children died on the same day, and she later divorced her husband. In the early 1960s, Aoko became known for her charismatic gifts; she baptised, exorcised, and healed people across Nyanza province. According to sources that underline her centrality in the Legio Maria, she had a vision of establishing an organisation called Maria Legio even before she encountered Ondeto. In her ministry, she often preached against smoking and alcohol use. She, Simeo Ondeto, and Mama Maria met for the first time in April 1963, and Gaudencia Aoko was granted special status because of her extraordinary charismatic gifts.

According to field studies and press reports from the early 1960s, neither Odeto nor his followers considered him the Messiah, but only a great prophet and healer; at least, it was not a widespread view. However, today, the official narrative clearly states that the founding of Legio Maria coincided with the adherents’ understanding that Ondeto was God. According to this latter view, which plays a central role in Odoo’s apologetic texts, on March 9, 1962, while in a private home in Suna, Migori, and very soon after having met Mama Maria, the Holy Spirit revealed that Christ had returned to Earth as Simeo Ondeto and that he was known as Baba Simeo Melkio Messias. This moment is known as the Legio Pentecost, when a ‘general outpouring of the Holy Spirit’ was experienced by more than a thousand people. Pope Romanus writes about this occasion:

A multitude of saints and angels descended from heaven into the home. They were the singers of the four songs. When they entered the home, they worshipped Simeo Ondeto, with each of them falling down on their stomachs and worshipping him. When we saw this, with each of us who experienced the ecstasy, rapture and heavenly visions sharing the same experience, we realized that Simeo is God.

After the event, Ondeto established his headquarters on the mountain of Got Kwer in Nyanza, which he and his followers referred to as the New Jerusalem and the Holy City.

The Institutionalisation of the Movement

1963 and 1964 were hard years for the Legios. The Kenyan authorities persecuted them, the Roman Catholic Church campaigned against them, and the spiritual centre at Got Kwer was destroyed. Apart from clashes with local Roman Catholics, in 1964, the Kenyan police arrested more than thirty leading Legios, including Ondeto, for holding illegal meetings and for breaking up families because of their unorthodox teaching. At the trial, the judge described them as ‘a collection of lapsed Catholics and pagans practising heresy that is a mockery to Christianity and the Roman Catholic Church.’ Still, after a debate in Kenya’s National Assembly, they were released from prison because they were not considered a threat to society. Additionally, the Roman Catholic Legion of Mary brought them to court over their choice of name.

In comparison, 1965 was a relatively calm year for the Legio, but in 1966 the violence escalated once more, reaching a new peak. However, in the same year, Legio Maria was officially registered as a church, and the large-scale persecution ended. Still, the experiences of these years play an essential role in the identity of the Legio Maria, and some of the Church’s holiest locations serve as memorials.

Among scholars and Legios, there is a discrepancy over whether Ondeto and his adherents understood his status as the Messiah at a particular moment or whether it was a gradual process. The majority did not know the story about the so-called Legio Pentecost in 1962. Not surprisingly, scholars tend to argue for a gradual change in his self-understanding. However, even in a rare video of Ondeto, he stated that he gradually came to understand who he was. However, at least since the second half of the 1960s, a central Legio doctrine has been that Ondeto was God incarnate. It can even be seen as the Legio’s primary teaching. Emphasising his divine status, he is referred to in many different ways, including Baba Messias, Baba Simeo, Baba Simeo Melkio Messias, Simeo Messias, Simeo Christo, Baba Simeo, and Lodvikus Melkio.

By 1963, the three founders of the Legio Maria–Ondeto, Mama Maria, and Gaudencia Aoko¬–ordained the first priests and consecrated the first bishops. The establishment of a parallel ecclesiastical structure meant an institutional break with the Roman Catholic Church. To a large extent, it was based on the Roman Catholic model, with a pope, cardinals, archbishops, bishops, priests, and deacons, as well as nuns, often called church mothers.

Another crucial step towards the greater institutionalisation of Legio Maria was the adoption of a formal constitution in 1964. According to this document, the Legio had two ‘extraordinary spiritual leaders’: Ondeto and Aoko. Apart from them, Mama Maria had an exceptional status, as she was the incarnation of the Virgin. The document is important because it shows the prominent position Gaudencia Aoko held within the church organisation at that time. It refers to her as ‘R[igh]t. Rev[erend] Mama’ and ‘Auxiliary Spiritual Leader of the Faith.’ The constitution says nothing about the divine status of Ondeto. However, the document was probably part of the process of becoming an officially recognised religious entity, and that context would not have made supernatural claims strategic.

In 1964, Ondeto and Mama Maria took yet another step: they elected Bishop Timotheo Blasio Atila (1941–1998) Pope and declared that he would succeed Ondeto when the latter returned to heaven. Until the death of Simeo Ondeto in 1991, he, as the Messiah, was the unquestionable leader, and Pope Timeo Blasio Atila had a subordinate position. On December 23, 1966, Mama Maria died, or in the words of the Legios, she ‘returned to heaven’ and is venerated as the saint par excellence. Explaining the status of Mama Maria, Deacon Odoo writes

While she is called Mother Mary (Mama Maria) and taken to be Virgin Mary, Legio faithful do not worship the woman. However, she is adored in the same way the Roman Catholic Church adores Virgin Mary. She is considered the greatest of saints and there are special prayers that are held by Legios in reverence to her.

By this time, in the mid-1960s, Ondeto gradually came to understand himself as Christ, and the church structure changed. In 1966, the Church held an Apostolic Council, which decided to bar women from the priesthood. The development led to internal opposition, not least from Gaudencia Aoko. In 1968, Aoko eventually left Legio Maria. Her reason was that women no longer should be able to serve as priests, but she also opposed Ondeto’s messianic claims. Having left Legio Maria, Aoko founded a church of her own, first called the Legio Maria Orthodox Church, then the Holy Church of Africa, and finally the Communion Church, a religious entity officially recognised by the state in 1971 and still in existence. Due to her ‘apostasy’, today semi-official Legio publications and clergy alike generally downplay Aoko’s role.

Hierarchy

During her fieldwork in the mid-1980s, Nancy Schwartz tried to systematise views on the hierarchical status of different groups in the Legio Maria. Her informants agreed on many points, but there were mixed opinions about the exact position of the church mothers, that is, which was the highest limit of formal female authority. More concretely, it concerned whether they had the same status as deacons or mass servers, roles reserved for males.

Pope (Pop)

Cardinals (Kardinal, kadinol)

Archbishops (Acbbisop)

Bishops (Bisop, askof)

Priests (padri, pi. Pate, also fadha, jaduong’)

Deacons (diakon) or Mothers (Madha, pi. mathe)

Mass-servers (Ototo misa, toto misa, pi. watoto misa) or Mothers ((Madha, pi. mathe)

Teachers (japuonj, pi. jopuonj), committee chairmen and chairwomen (jakom, pi. jokombe)

Brothers (bradha, pi. brathe)

Sisters (sista).

Schwartz’s documentation of formal ecclesiastical authority provides ample evidence of the limited formal power of women in the Legio Maria after the very first years. Still, church mothers receive a kind of ordination, and, due to unusually strong charismatic gifts, some church mothers hold positions equal to those of priests or even bishops. It is a frequently expressed view that male clergy represent Christ, while church mothers represent the Virgin Mary. There is also an internal female hierarchy, reaching from sister to mother, superior, arch-mother, and dean mother. Schwartz also writes.

“The spirit can lead Legios to acquire robes of yellow, a range of blues, purple, green, red, brown and other colours that are associated with various spiritual gifts and patron saints. Black is for ordained male priests (padri, pl. pate) and church mothers (madha, padri madhako, pl. mathe, pate mamon). Legio priests and church mothers wear black robes at requiem masses and at graveside services held in family compounds. At happier times, black prayer beads are worn or carried by church mothers and priests as a metonym of power and ordained status. A few non-ordained men and women said they had the black beads on their house altars because a dream had directed them to get the beads and pray with them at home. The dream-bestowed black beads were a source of quiet pride to these Legios.”

References

A webpage related to the Legio which includes a chronicle and explanations of beliefs: http://legiopedia.com/

Another informative website related to the Legio: http://lejionmaria.blogspot.se/

Dirven, Peter. 1970. “Maria Legio: The Dynamics of a Breakaway Church among the Luo in East Africa”, PhD Dissertation, Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome, 1970.

Hinga, Teresia M. 1990. “Women, Power and Liberation in an African Church: A Theological Case Study of the Legio Maria Church in Kenya”, PhD dissertation: Lancaster University

___. 1992. “An African Confession of Christ: The Christology of Legio Maria Church of Kenya” in: Teresia M. Hinga Exploring Afro-Christology. Bern: Peter Lang.

Kustenbauder, Matthew. 2009. Believing in the black Messiah: the Legio Maria Church in an African landscape. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 13(1): 11–40.

____. 2012. “Aoko, Gaudencia”, in: Emmanuel K. Akyeampong & Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (eds), Dictionary of African Biography, Volume 1: 245–247. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ol’leka, Shitandi Wilson 2010. “An Analysis of Musical and Theological Meaning in the Hymnody of Legio Maria of African Mission Church in Kenya”, PhD dissertation, Kenyatta University.

Moreau, Scott, & Kombo James, “An Introduction to the Legio Maria,” African Journal for Evangelical Theology 10.1 (1991): 11–27

Prince, Ruth. 1999. “The Legio Maria church in Western Kenya: Healing with the Holy Spirit and the Rejection of Medicines”, PhD dissertation, University College London.

Schwartz, Nancy. 1989. “World Without End: The Meanings and Movements in the History, Narratives, and ‘Tongue-Speech’ of Legio Maria of African Church Mission Among Luo of Kenya.” PhD dissertation. Princeton University.

___. 1994. “Charismatic Christianity and the Construction of Global History: The Example of Legio Maria”, in: Karla Poewe (ed.), Charismatic Christianity and Global History, pp. 134–174. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

___. 2000. “Active Dead or Alive: Some Kenyan Views About the Agency of Luo and Luyia Women Pre-and Post-Mortem. Journal of Religion in Africa 30.4: 433–467.

___. 2004. “Ragot, Mariam”, in: Phyllis G. Jestice (ed.), Holy People of the World: A Cross-Cultural Encyclopedia, vol. 3: 717–718. Santa Barbara: ABC Clio.

___.2005. Dreaming in Color: Anti-Essentialism in Legio Maria Dream Narratives, Journal of Religion in Africa, 35.2: 159–196.